Were Read to Achieve Passages Updated in 2017-2018

Beth Rivera felt similar a rock star. She was interviewing for a instruction position in Wedlock County Public Schools, where the district was focused on a "balanced literacy" arroyo to teaching young kids to read.

Rivera was fresh off a chief's degree in literacy from the Teachers College at Columbia University, where her professor was Lucy Calkins, whom Rivera calls the queen of balanced literacy.

"My school district was aught short of thrilled to have a real-life, in-the-flesh Teachers College reading and writing practiced in their midst," Rivera said. "What a boost to my self-esteem."

The balanced literacy approach combines a little language education with whole-group, small-group and independent reading exploration. While at that place isn't one balanced literacy method, a common example involves demonstrating three means of cueing readers to guess words through significant, syntactical and visual information. Calkins' curriculum is widely used throughout the nation, and, as of last year, balanced literacy teaching was in a bulk of Northward Carolina school districts.

Rivera was overjoyed, and more than than a fiddling surprised, when the district asked her to go into other class-level classrooms to model counterbalanced literacy educational activity for her peers.

Simply the joy didn't last long.

She noticed some students in her class every yr that she couldn't reach. The reading light bulb wasn't turning on for them, and she couldn't figure out why. Although puzzled, she pressed forward. A few years later, the trouble took root in her own dwelling when her son, Brendan, started coming home talking about his "bad encephalon."

"Mommy, my brain only doesn't exercise what I want information technology to," he told her.

After a mini-lesson from the teacher in his class, students would render to their desks to read by themselves. Brendan would just sit there.

"He had no idea what he was supposed to do," she said.

The school said he was immature. Give him time. Even her husband idea he'd take hold of up somewhen. Simply Rivera wasn't satisfied.

"Every bit a teacher, I was seeing signs I couldn't ignore," she said. "He'd recognize the discussion 'what' on folio 2 of his volume, and and so that same word would appear on page half-dozen and he'd tell me he didn't know that give-and-take."

One day, the word "flashlight" came up. Brendan said he didn't know that word. Rivera looked at him and, reaching for her training in balanced literacy, started prompting him to guess based on pictures and the context of the story. But he was stumped.

"I realized that I had spent nearly $40,000 on a piece of paper that declared that I was a chief of children's literacy," she said. "How am I a master if I can't aid my ain son? I started to question everything."

The questions led Rivera to the science of reading. This is a trunk of inquiry from psychologists, linguists, and neuroscientists — all dating back more than than 30 years and detailing how cognitive scientific discipline says kids learn to read. It led her to the conclusion that balanced literacy is not right for many students and that an explicit, systematic approach with a phonics-foundation could work for nearly everyone.

She too came beyond a 2018 audio documentary past a journalist named Emily Hanford, whose work has made the science of reading accessible. Her reporting has prompted a resurgence of back up behind using scientifically proven methods to teach literacy — including in Due north Carolina, where counterbalanced literacy dominates while reading scores disappoint.

A growing coalition of Due north Carolina leaders wants to reform literacy instruction to align with the science of reading. A move, which started as whispers when reporting for this story began in March, is growing louder through discussions and activeness plans shared at the General Assembly, State Board of Educational activity, and the Department of Public Pedagogy.

Proponents say the right instructional practices will help more N Carolina children larn how to read and also plow around the Read to Achieve law, which has failed to produce improvement despite its $150 million price tag.

"We're moving toward that science, and you lot'll come across information technology in our budget requests for the curt session" in 2020, Land Board member JB Buxton said. "Yous're going to see requests around reading coaches that the land will hire. You're going to encounter requests for appropriations that would allow us to practise grooming for teachers, principals, and banana principals on the science of reading. We're going to need some back up from the General Associates when it comes to resource that go beyond what's in the Read To Accomplish, only given their strong support for that, we're going to exist able to build a strong example."

This grouping of teaching leaders back their case with a carefully crafted State Board literacy framework and cross-divisional DPI steering committee, both of which took shape and sharpened in focus over the several months EdNC reported this story. And that framework cuts ties with ineffective reading strategies and moves toward both the science of reading and comprehensive policies implemented by states that congenital successful literacy reform — like Mississippi.

Does instruction based on the science of reading actually piece of work?

Read to Reach was passed in North Carolina in 2012. Mississippi's reading law, the Literacy-Based Promotion Act, was passed i yr afterwards. But while North Carolina'south reading scores are stuck, Mississippi's are rising. A lot.

Since October, Mississippi has garnered headlines for making more than progress than any other country on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. In fact, Mississippi was the just state to testify pregnant gains in fourth-course reading scores.

And Mississippi is doing it with much less money than North Carolina. In seven years, Mississippi has spent less than $100 million under the law. Reading proficiency began showing marked improvement after its second year — but $24 million into the experiment.

In 2015, 92% of third graders passed the country's reading examination. In 2016, the state significantly raised its standards for a passing grade. All the same, last yr nearly 83% passed.

In the first yr of North Carolina's Read to Achieve legislation, the passing rate on tertiary-course reading exams was 60.2%. Last year, information technology was 55.9%. A report produced past N.C. Land University'southward Friday Establish showed that in some grades the reading scores were stagnant, while in other grades they were falling.

What makes Mississippi's police force and then much more effective? Kymyona Burk points to the science of reading, and she should know. Mississippi's ascent happened nether Burk's leadership as manager of literacy at Mississippi'southward Department of Education.

"The affair most our law is that it was specific enough to name the scientific discipline of reading," she said. "There are states that passed their constabulary and and then they waited, in effect, for information technology to take whatever teeth in it. But what happened to the money that you all pumped into it?"

The Mississippi law gave its Department of Teaching the ability to train teachers in programs aligned with the science of reading and to provide literacy coaches, hired by the state, to sit in residence at schools for an entire year.

"When people enquire me what programs did nosotros employ, I tell them we invest in people — not programs," Burk said. "When you increase their cognition about the scientific discipline of reading and what it takes to teach reading to children, then they begin to adopt programs aligned with that."

The state provided training, using a significant portion of the upkeep. Mississippi provided early literacy professional development to teachers, principals, and ed prep professors using the science-based Language Essentials for Teaching Reading and Spelling (LETRS) program designed past Louisa Moats and Ballad Tolman. Since 2014, more than 14,000 educators have received LETRS professional evolution.

"So yous go dorsum to the coaches who are on site and say, 'OK, at present that yous've had this LETRS training, let's transfer that into practice with your students,'" Burk said.

The state hired 22 coaches that first year, preparation them in science-aligned practices, observing their ability to work with others, and sending them into the lowest-performing schools. That was seven years ago. Now, the number of land-hired literacy coaches is 82.

The ability to brand decisions at the land level, Burk said, was crucial. And she credits other land leaders for supporting her. She was in abiding contact with her land's superintendent, too as the Republican governor, Phil Bryant.

"And to say I'm a Democrat — I'm a black girl leading literacy in Mississippi, OK," Burk said through a laugh. "Only this isn't a partisan issue. To have a sit down-downwardly with the governor several times, for him to go on asking me what exercise I need. Nosotros worked together, and they empowered united states."

Beyond the governor, Burk pointed to the section's master bookish officeholder — whom she chosen an thought fairy who made all her ideas come truthful. She also said support from her state superintendent "was everything."

In contrast, unity seems fractured around Read to Achieve amid North Carolina's officials — betwixt the State Lath and Superintendent of Public Instruction Marking Johnson, specifically. Merely last calendar week, Johnson accused the State Board of "aggressively" undermining Read to Reach's directives. He sent a memorandum calling out the board for promoting lxx,000 students who hadn't passed third-grade reading exams to 4th grade.

"The NC State Board of Pedagogy was tasked with implementing the Read to Achieve legislation," he wrote. "Read to Achieve specifically directed the State Board of Education to cease social promotion of 3rd graders – promoting students from ane grade level to the next on the basis of age rather than bookish ability. Sadly, the State Board'southward policy aggressively avoided that directive."

Burk agrees that holding to performance-based promotion helped Mississippi's students, but she doesn't think that'southward the main reason reading scores have skyrocketed.

"If you're going to hold them back, nosotros had to make sure we had teaching in identify that would help them learn to read," she said.

And that assurance, she says, lies in the reading science.

Why does the science behind reading matter?

For more than a century, researchers accept argued over how people acquire to read. Most of the disagreement has centered on children figuring out how to decipher words on a folio.

Phonics was pop for decades. The approach teaches children that words are made upwards of parts and focuses on how different letters and combinations of messages connect to the speech sounds in words. Phonics was tagged with a reputation for beingness mechanical and boring, though, and another theory — called whole linguistic communication — gained popularity.

People soak upwardly spoken linguistic communication like a sponge from the fourth dimension they are babies. We learn to talk through exposure to conversations. Whole language assumed that reading would work the same mode. So if children are exposed to good books, kids should pick up reading on their own. It was designed to foster a love for reading and encourage kids to reach for the significant of passages rather than focusing on words.

"This means that if we accept it apart to focus on letters, lists of words or grammer patterns, we lose the essence of what language is," one periodical article on whole language pronounced. "Reading should not be taught as the isolated skill of connecting symbols and sounds. Learning to read must also be connected to life experience, meaningful activities and the learner's goals through discussion, speaking, listening, and writing."

Simply phonics proponents — and the scientific enquiry — said that reading is not natural. Our brains are not wired to read. Nosotros have to be taught to decode words. In the 1990s, the debate over the best arroyo became intense. One article referred to it as the Reading Wars.

Congress convened a national reading panel in 2000 to written report the all-time ways to teach reading. That console concluded that there was a lot of scientific discipline to back upwardly an approach emphasizing word decoding, and none validating whole language.

In response, the whole language community tried to motility toward center ground. They called the new approach "balanced literacy." The idea was to innovate a little scrap of phonics pedagogy to the whole language approach, but non so much that information technology would bore kids or distract from finding meaning and connection.

"In balanced literacy, phonics is treated a bit similar salt on a meal," Hanford says in her audio documentary, Difficult Words, "A little here and there, but not also much, because information technology could be bad for you."

In April, EdNC got a first-hand await at a balanced literacy didactics.

A first-form teacher began her reading period with a mini-lesson for the unabridged class. She used an overhead projector and let students "walk the book" — looking at all of the pictures and guessing what was happening in the story. Side by side, they read the book together, page-past-page. On each page, they returned to the picture show first and so tackled the sentences.

The students came confronting the sentence, Everything outside is cold in winter.

"Would I see snow in the summertime?" the teacher asked earlier a chorus of no.

"When would I unremarkably run across snow? What time of year?"

"Winter," a immature girl said.

"Let's do a double bank check on that give-and-take," the teacher said. "What does 'winter' start with?" She paused while the kids connected "winter" with the letter "w," then said the alphabetic character aloud in a chorus.

The teacher so broke up the word and highlighted the sounds. "I likewise see another part of the word that I know," she said. "I'm going to evidence you. What does -er say?" The students answered, and the teacher then covered the -ter, asking, "What give-and-take exercise y'all see?" The students shouted, "Win!"

The students seemed engaged and happy. And teachers at the school spoke excitedly about the their Calkins-based arroyo, which they implemented years ago in hopes of providing the all-time instruction for their kids. Just this was the aforementioned arroyo that wouldn't work for Rivera'due south son, Brendan, or for the students each year she couldn't accomplish.

"What happens if they come across reading where there aren't any pictures, or the pictures don't cue them on a discussion they are struggling with?" Rivera asked. "What if that happens on a reading examination?"

Tara Galloway is the manager of One thousand-3 literacy at DPI. Her arrival a twelvemonth agone marked a major shift toward instruction using the science of reading.

"I saw going into the classrooms that balanced literacy was rampant in N Carolina," said Galloway, who was exposed to the science of reading in ed prep and spent twenty years using explicit instruction as a special education teacher. "They were education them to look at the pictures and pedagogy them to apply cues that were ineffective. I said, 'We need to practise something most this.'"

What counterbalanced literacy left out from its phonics instruction, it turns out, is pretty important stuff.

In a recent Education Week article, reporters Sarah Schwartz and Sarah Sparks explicate information technology well: "Written language is a code. Certain combinations of letters predictably correspond certain sounds. And for the last few decades, the enquiry has been clear: Teaching young kids how to crack the code—teaching systematic phonics—is the most reliable manner to make sure that they learn how to read words."

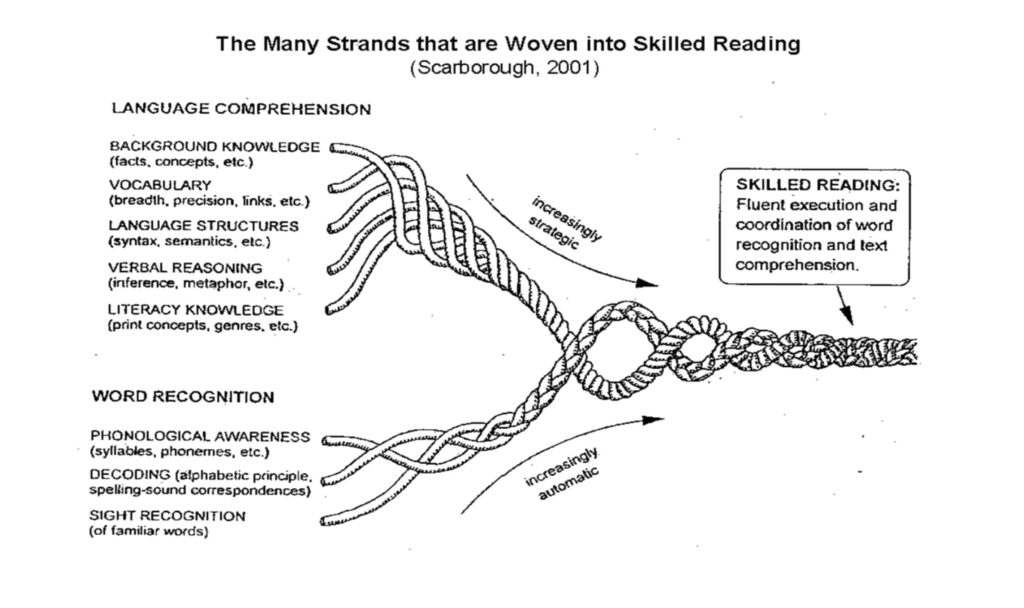

Hanford, who bases her reporting on poring through more than than three,000 pages of enquiry and studies and hundreds of hours talking to experts in literacy, followed Difficult Words with this year's audio documentary,At a Loss for Words. In it, she talks about a literacy model published in 1986 called the Simple View of Reading. Information technology asked questions similar: How does reading comprehension happen? And what's the function of phonics and decoding in all of that?

"The Uncomplicated View of Reading is a model that is now been backed up by lots and lots more research," Hanford said. "Information technology has a solid scientific base behind it and information technology essentially says, reading comprehension is the product of your language comprehension — the words you know how to say, the words you can hear — and your decoding ability."

Product. As in: Language Comprehension x Decoding Ability = Reading Comprehension. That means that a child who knows how to decode words won't become a skilled reader without exposure to a lot of books. Simply it likewise means that a child who is exposed to a lot of words and books however won't be a skilled reader unless someone teaches that child how to decode words.

It's a reminder that when experts talk about the science of reading, they're not talking well-nigh phonics simply. They're talking about phonics — phonological and phonemic awareness — as a foundation, in add-on to exposure to reading.

Most children brainstorm their pursuit of reading by learning the alphabet. But while English language words are made up of combinations of the 26 messages, decoding words has much more to do with something called phonemes — units of audio. There are 44 phonemes in the English linguistic communication. Some words, similar "a" or "oh," accept merely one phoneme. Others, like check (ch-e-ck) take three. If you lot visit the classroom of someone teaching reading according to the scientific research, you're more likely to find a "sound wall" displaying all the phonemes than a affiche of the alphabet.

Learning how messages make up sounds, how those sounds brand up words, and how to dispense those sounds to form and read words is a gateway into learning to read. It's decoding. And that foundation can help readers and so thrive through the vast exposure to books.

"The hallmark of skilled reading is you very, very chop-chop and very accurately know exactly what a word is when information technology's flashed in front of you," Hanford said. "In fact, scientists have done these studies which have showed that if you flash, in front of a skilled reader, the give-and-take 'chair' and the moving-picture show of a chair, your brain actually processes the pregnant of the discussion 'chair' quicker than the picture of a chair.

"Our brains weren't meant to do this, but when you get a skilled reader, yous get actually, really proficient at it. And so one thing I retrieve that teachers really need to sympathise about all this is that the goal is automatic recognition of words, but we do not recognize them equally wholes. When you and I are reading words, we are very speedily processing every unmarried sound, every single letter in that word. Then that is a hallmark of being a good reader."

This is a process chosen orthographic mapping. And it could hold the key to producing better readers and, past extension, better reading scores in North Carolina.

Growing consensus in N Carolina effectually scientific discipline of reading

Early on this year, Buxton — the State Board member — started drafting a framework for literacy reform modeled later the Mississippi law. It was grounded in discussions with members of the State Board, presentations to that lath, recommendations from literacy experts, what the data were showing, and consultation with DPI — especially through Galloway.

The participants reached a consensus on ix points for the framework — which is now a State Board certificate called Guiding Collaborative Framework for Action on Early Reading.

On the surface, things still seemed status quo on the reading front end. Quietly, though, the seeds of alter were existence planted and a coalition for change was forming around a common mission.

"We had to stop putting hurdles in front of kids or teaching them ways to slowly become over the hurdles," Galloway said. "We demand to just commencement moving the hurdles out of the way. Pedagogy reading based on the scientific discipline of reading does that."

Nearly this fourth dimension, in the bound, Buxton began working with Sen. Phil Berger, the architect of Read to Accomplish, on revisions to the law and calculation the "teeth" that Burk referred to before. Information technology was meant to be the legislation that would marshal N Carolina with the reading science, expert consensus, and data.

Buxton was a high school instructor and has spent many years working in politics and pedagogy policy. Reading was always a piece of his work, but he says it was never a centerpiece agenda item the way it is now. His deep dive into scientific discipline-backed literacy educational activity happened this past yr.

As he learned nearly the science, and the reforms in other states, he began putting that knowledge into piece of work. Sen. Berger filed the legislation in Baronial. Information technology was stamped Senate Bill 438.

Buxton was impressed with the consultants Berger and his squad brought in for help — including literacy expert Barbara Foorman, former commissioner of the National Eye for Instruction Inquiry at a U.S. Department of Education institute. Foorman had been invited to open up North Carolina's K-3 Literacy Briefing and Reading Summit in March.

"And I realized that nosotros were all talking well-nigh the aforementioned things," Buxton said. "And we weren't having disagreements near what the loftier-leverage focus areas needed to exist."

SB 438 was ratified in August and presented to Gov. Roy Cooper. Nine days subsequently receiving it, though, Cooper vetoed information technology.

Buxton doesn't believe Gov. Cooper had a problem with the substance of the proposed legislation. The upshot was whether DPI had the bandwidth to handle the implementation. This was only weeks after scrutiny over DPI's choice of Istation as the reading assessment vendor under Read to Achieve erupted.

"There was a existent concern that we had a major, new set of revisions in the Read to Attain police force, a lot of which would take to be handled by the department and, at least from what I was hearing, a existent concern about the capacity of the department to exercise it well," Buxton said. "I understood those concerns. I don't call up it was disagreement by the governor with some of the specific changes to the police."

If the veto was a setback, though, it was a momentary ane. Leaders including Buxton, Galloway and Galloway'southward boss, Deputy State Superintendent David Stegall, pressed forwards — determined to find another way to launch these strategies.

"I would have loved to accept seen the legislation get through considering it provides the changes we need to make it effective," Buxton said. "[The veto] certainly meant we were going to take to wait at some different pathways to put some things in identify. It would accept been overnice to have some provisions in the police force that now we're going to have to call back about how to do through Board policy and department and administrative action."

Simply even if it meant a longer road, Buxton says one of his principal takeaways from working on the legislation is that Northward Carolina is in the midst of a moment — a moment we tin can look dorsum on and say something special started here.

"Having spent a lot of years in public education in North Carolina, y'all run into issues move when information technology's almost similar an repeat bedchamber," he said. "Where everybody's talking well-nigh the same thing and yous see much more alignment when that happens. I'k bullish on this moment."

A framework for change in N Carolina

Over the years, and even at this moment, at that place are multiple literacy plans floating around the DPI building on Wilmington Street — some completed, some still in draft form. The one consulted most comes from the Read to Achieve police, but that hasn't produced much focus. The Friday Plant'due south report on Read to Achieve said it "appears to exist 115 different pilots operating under a few common parameters."

Leaders calling for change want more construction and guidance to set teachers and students upward for success.

"Nosotros've got to get to an agreement on how nosotros're going to teach reading," said Eric Davis, chair of the Country Board. "And then, how nosotros're going to gear up teachers to teach. And, if we tin can go that done, nosotros accept to become agreement on what curriculum we're going to apply. At that place's no actually well-defined, research-based strategy now."

Buxton said that one thing the original Read to Reach neb did non accept "was acceptable teacher supports. And that's what the new [vetoed] neb was moving towards, and we've got some boosted pieces that we're going to be making the case for now likewise."

That instance will be made through the State Board's nine-point Guiding Collaborative Framework and a B-12 Steering Committee that Galloway has been quarterbacking. The steering committee has "cross-bounded/cross-surface area involvement" including 5 different directors at DPI.

Over the next several months, and perchance years, Galloway volition nowadays updates, action plans and recommendations to the State Board — starting in January. The framework volition guide country efforts across nine initiatives.

1. Develop a statewide definition of loftier-quality reading educational activity.

This is the subject field of Galloway's first report to the Lath, to be presented in about iv weeks. DPI held iii regional stakeholder meetings to gather feedback on a working definition of high-quality reading instruction. They talked with administrators, advocacy groups, ed prep professors at universities, teachers, parents and country leaders. Prior to the January update at the State Lath, DPI is requesting feedback from the public through a survey.

"You've got to be on the aforementioned page well-nigh what skilful reading instruction looks like to and so define what your professional development is going to look like, what your teacher preparation is going to look like, all of information technology," Buxton said. "That's going to exist in January."

2. Improve focus on reading educational activity in teacher preparation programs.

The next priority will be executed past an early on literacy job force chaired past Ann Clark, former Charlotte-Mecklenburg superintendent and board member for the Belk Foundation. The task force will hold its first coming together December 20. It aims to ensure ed prep programs are providing sufficient instruction, modeling and practice in three focus areas: the science of reading; the review and option of high-quality reading curriculum; and in working with struggling readers with diverse learning needs.

Buxton said some of the recommendations for instructional programs that districts will utilise, such as LETRS, volition come up from this group.

iii. Meliorate summer reading campsite quality.

Summer reading camps were introduced under Read to Achieve to curb summer learning loss and provide students actress teaching. Galloway and one of her regional literacy consultants, Tonia Parrish, said the camps needed more support and guidance. Terminal yr, Parish worked on improvements, such as providing camp hosts with online modules on science-of-reading practices. She is now working on making those modules more robust.

4. Provide reading motorcoach supports in low-performing schools and districts.

This priority is about providing reading coaches in select schools, such as turnaround schools in the bottom 5% of state performance scores, who would be hired and managed by DPI (in partnership with local schools and districts). Priority actions will include developing a budget that supports hiring and training coaches.

five. Expand partnerships to support beginning teachers.

This initiative would expand efforts with universities in select regions of the state, focusing on back up for get-go teachers in grades K-3. The types of supports would include intervention and coaching on reading, ensuring high-quality curriculum, and building sustainable systems of instructor development.

half dozen. Ensure high-quality reading curriculum and instructional materials in elementary schools.

Fifty-fifty as Burk says Mississippi focused on teachers more than than programs, she underscores the importance of the right curriculum and programs. This priority focuses on making sure that reading curriculum, instructional materials and supports are aligned with land standards and reading science.

It's critical, Buxton said, "considering if you're a second-grade instructor, especially if you're new, y'all can't be asked to figure out a way to put a series of lessons together or a series of modules. You shouldn't be asked to expect on the Internet, Pinterest, all these places to find proficient stuff. You need a loftier-quality curriculum that supports you in meeting these standards."

This initiative would develop a budget to provide resources for districts that need help buying curriculum and instructional materials, also as for training and coaching.

7. Explore a statewide organisation of training in reading for teachers, principals and reading coaches on the scientific discipline of reading.

Having the right curriculum and graduating new teachers trained in reading science won't help, Galloway said, without continued support. The B-12 Literacy Team and State Lath are exploring a statewide system for training on the science of reading, loftier-quality curriculum and evidence-based interventions for principals, teachers, and reading coaches. It will also look at how a arrangement of training would address non-native English speakers and consider culturally responsive approaches.

The North Carolina State Comeback Projection (NC SIP) currently offers some training in the science of reading, and the priority is to build on that training.

8. Provide flexibility in land funding to back up district action on reading.

This would provide districts with flexibility to accept unused summer reading camp money and put it toward evidence-based supports such as reading coaches, reading tutors, high-quality reading curriculum, or professional development focused on the scientific discipline of reading for Thou-3 teachers. Districts also could transfer funding between allotments for Thou-3 teachers, instructor administration, and textbooks to support high-quality plans for reading.

ix. Ensure admission to high-quality PreK and strong early learning environments and transitions to kindergarten.

Under this priority, the state would wait to support local planning for expanding admission to high-quality Pre-Thou, back up community partnerships and family unit date and focus on transitions to kindergarten.

High stakes riding on reform, from disinterestedness to basic homo rights

"Literacy is a crucial part of the foundation of a thriving and prosperous customs," said Kris Cox, who was a public schoolhouse instructor before becoming executive director at READWS, or Read⋅Write⋅Spell in Winston-Salem. READWS is a nonprofit that tutors students and consults with schools on structured literacy — which is a term the International Dyslexia Association uses for reading approaches rooted in the science of reading.

"The right to read is a basic, fundamental human right," Cox said. "The perpetuation of illiteracy leads to heavy and often tragic consequences via lower earnings, poor wellness outcomes and higher rates of incarceration."

In other words, this is an equity effect.

As Rivera tells it, it's a matter of using reading instruction that reaches the virtually students — because not every family tin beget to spend coin outside of public schooling to learn the keys for unlocking reading. Nor should they need to, as Mississippi exemplifies. It'south turning out the nation's best reading results on NAEP despite having the highest poverty rate of the 50 states.

After she devoured piles of enquiry on the science of reading, she enrolled her son at a individual school in Charlotte. In that location, she watched him go from a struggling to thriving reader. She was grateful, but her gratitude was clouded by regret and anger. She couldn't shake the idea of how many students she had been unable to reach through counterbalanced literacy. And she was angry at her master's program, and particularly at Calkins — her advisor and instructor.

With hands shaking, she penned a note to Calkins asking why — why didn't Calkins ever tell her about the scientific enquiry?

"I never heard annihilation back," she said.

Calkins did non grant an interview for this story, just she did reply by e-mail referencing a recent webinar that she did saying, "I think getting this right for the sake of kids is important." The webinar is hosted on Instruction Week's site but sponsored by Calkins's publisher, Heinemann. Calkins also posted an article this calendar month, entitled "No One Gets to Own the Term 'The Science of Reading.'" It has since garnered a lot responses, such as this open letter, from those in the science of reading customs.

Meanwhile, Rivera moved on from waiting to hear from her old advisor. And she was fed up with choosing betwixt private school tuition and a public school that used counterbalanced literacy. Her family moved to Upper Arlington, Ohio, where the district'south reading curriculum is aligned with reading science.

"Today, my son knows more than about the rules of the English language language than well-nigh of the reading and writing teachers out at that place exercise," Rivera said. "He can tell you why we double the consonant in "blubbering." He tin tell y'all why we learn how to divide words into their syllables, so you know what the vowel says and tin can then decode the word. He knows that the audio /k/ at the end of a discussion is e'er going to exist spelled with a "ck," because "ck" comes at the end of a one-syllable word after a curt vowel.

"These are the keys to our language. Brendan may not read equally quickly or as fluently as his peers, just he can read. He can decode. He can encode. Everyone should have that opportunity."

This commodity originally attributed a quote to journalist Emily Hanford. The quote is now properly attributed to this Education Week commodity.

This commodity originally contained the statement: "The B-12 Steering Committee will likewise be looking to find a more robust and ongoing grooming than NC SIP can offer." This data did not come from anyone on the B-12 Steering Committee.

Source: https://www.ednc.org/a-wall-of-sound/

0 Response to "Were Read to Achieve Passages Updated in 2017-2018"

Post a Comment